AUKUS+? Seoul’s Nuclear Submarine Gamble And The Future Of Asian Geopolitics

By Uriel Araujo

South Korea’s long pursuit of nuclear-powered submarines now coincides with Washington’s shifting alliance strategy. Analysts see an emerging AUKUS+ system as Seoul ramps up spending and regional powers reassess their posture. Indonesia, ASEAN, and India, in contrast, add complexity by resisting rigid bloc politics.

As Washington, Canberra, London, and now Seoul deepen their military ties, a question that once seemed hypothetical is suddenly urgent: is South Korea about to become the next pillar of an AUKUS-plus architecture? The recent flurry of announcements — including Trump’s approval of a Korean AUKUS-style framework, joint discussions on nuclear submarine construction, and Seoul’s massive new defence-spending pledges all impact on the Indo-Pacific’s strategic map.

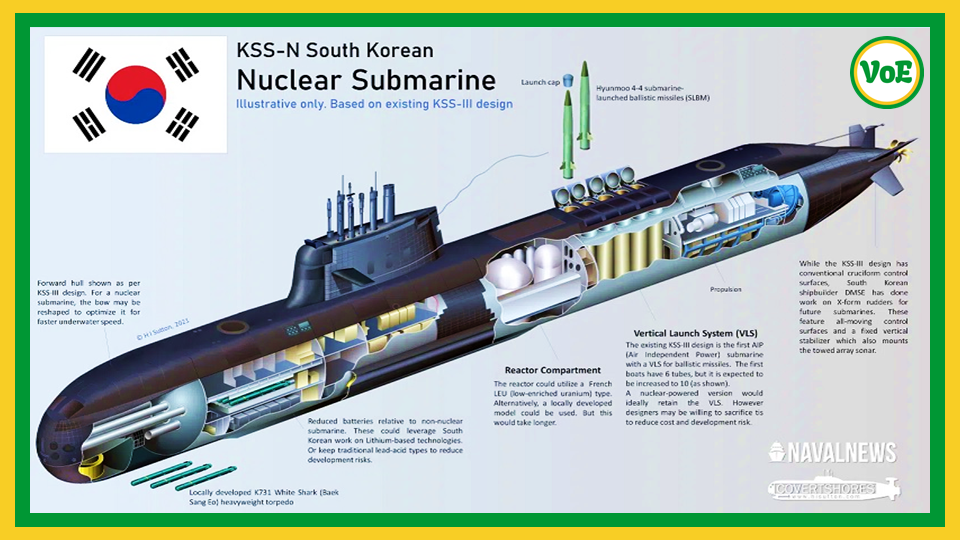

Some analysts are commenting that South Korea’s 30-year quest for nuclear-powered submarines is finally “paying off”. The program is largely US-built and US-directed thus tightening bilateral interdependence in ways that go far beyond traditional alliance management, as Seong-Hyon Lee (associate-in-research at the Harvard University Asia Centre) notes.

Meanwhile, Seoul is preparing to spend $33 billion to support US forces while buying $25 billion in American weapons, though no official clarity exists on where the nuclear subs will be assembled.

Thus far, the move has generated more questions than answers. Sam Roggeveen (Program Director of the Lowy Institute’s International Security Program), for one, described the whole submarine initiative as a “mystery,” raising questions over whether Trump has promised more than Washington is prepared to deliver. Enough ambiguity surrounds the timeline, safeguards, and industrial capacities that analysts wonder whether AUKUS itself is being somehow quietly “outsourced” to Seoul.

Trump’s “America First” rhetoric is paradoxically leading to deeper dependence on allies. As I argued earlier in my analysis of AUKUS and Australia’s militarization, Washington is shifting from direct burden-bearing to burden-shifting — outsourcing production, logistics, and even deterrence. One may recall that similar dynamics have plagued the Quad. Its current stagnation, as I previously wrote, results partially from Trump’s neo-Monroeist instincts: he wants partners to pay more, align more, and deliver more.

Suffice to say, South Korea fits well enough into this model. Unlike Australia — whose AUKUS commitments already strain its shipyards and budget — Seoul possesses a strong industrial base capable of nuclear-submarine co-development. Japanese shipyards too have the potential, and debates in Tokyo now reflect growing willingness to align more closely with AUKUS-style frameworks. No wonder American lawmakers are floating scenarios of expanding submarine production into Northeast Asia.

Be as it may, any such expansion carries risks. Chinese and Japanese naval planners have already warned that Seoul’s entry into the nuclear-submarine club could accelerate their own programs. Regional nuclear-proliferation concerns are escalating as well, with Chinese analysts describing the US-South Korea cooperation as clearly weakening the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

According to Seong-Hyon Lee, as mentioned, South Korea is no longer merely “buying” US security; it is building a system of strategic interdependence that binds both states more tightly than ever. Thus, the Korean version of AUKUS may actually be the ultimate expression of what the US expects from its allies today: deeper integration with US defence supply chains, increased purchases of American systems, and alignment with Indo-Pacific deterrence strategies.

Yet while Washington pushes forward, Seoul faces major fiscal limits. Domestic pressures are rising, and its pledge to raise defence spending to 3.5% of GDP clashes with tightening budgets and demographic constraints.

Moreover, these submarine arrangements may expose South Korea to new escalatory pathways. Japan’s debates on acquiring its own nuclear subs — once taboo — are intensifying. North Korea in turn, already sensitive to American military cooperation with the South, will likely respond with further missile tests. And East Asian diplomatic channels, fragile enough already, may suffer another blow.

But there is a larger, underreported angle here, one that cuts across a clear North–South cleavage: northeast Asia’s militarization unfolds just as Southeast Asia embraces multi-alignment. As I recently wrote about Indonesia and North Korea, ASEAN states — notably Indonesia — prefer autonomy to bloc politics. They keep communication lines open even with Pyongyang, prioritize sovereignty, and resist zero-sum alignment pressures.

This is the Indo-Pacific paradox: while Washington encourages rigid security blocs, regional powers explore flexible coalitions instead. So much for the notion of a unified anti-China front. India, for one, hedges between Eurasian and Pacific ties; ASEAN bets on soft diplomacy; and Indonesia even contemplates low-risk cooperation with North Korea.

In this sense, the emergence of “AUKUS+” may harden blocs in the north while promoting multi-alignment in the south. The Indo-Pacific therefore becomes not a single theatre but a mosaic of overlapping power centres.

In any case, with nuclear transfers to non-nuclear states, expanding submarine alliances, shipyard capacity constraints, and widening NPT concerns, the Indo-Pacific’s nuclear shadow is lengthening. Critics argue that AUKUS already pushes the Non-Proliferation Treaty to its limits, encouraging emulation. South Korea joining AUKUS+ may widen Washington’s footprint, giving it more strategic depth, but it risks igniting an arms race.

Some say Trump’s approach is erratic enough that the entire configuration could shift again tomorrow, and that could be a fair point. But the broader trend remains unmistakable if one looks at patterns: burden-shifting, alliance outsourcing, nuclear proliferation concerns, and tighter US-allied interdependence.

Be as it may, the Indo-Pacific is changing fast — and South Korea’s nuclear-submarine leap could mark a point of no return.

Uriel Araujo, Anthropology PhD, is a social scientist specializing in ethnic and religious conflicts, with extensive research on geopolitical dynamics and cultural interactions.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Voice of East.

Discover more from Voice of East

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Analysis, Geopolitics, International Affairs

Brazil-Russia Nuclear Diplomacy Challenges Washington’s Hemispheric Dominance

Brazil-Russia Nuclear Diplomacy Challenges Washington’s Hemispheric Dominance  Trump 2.0 Must Urgently Declare Its Position Towards Poland’s Nuclear Weapons Plans

Trump 2.0 Must Urgently Declare Its Position Towards Poland’s Nuclear Weapons Plans  A Venezuelan‑Style Iran Oil Blockade Could Let The US Divide And Rule RIC

A Venezuelan‑Style Iran Oil Blockade Could Let The US Divide And Rule RIC  Poland’s Anxiety Grows Over The Future Of U.S. Troops On Its Soil

Poland’s Anxiety Grows Over The Future Of U.S. Troops On Its Soil

Leave a Reply